Grayton Beach State Park: Ultimate Guide to Conservation

Guide to Grayton Beach State Park’s conservation: habitats, restoration, endangered species protection, and visitor rules to protect dunes and Western Lake.

Grayton Beach State Park is a 2,000-acre sanctuary along Florida's Scenic Highway 30A, safeguarding rare ecosystems like coastal dune lakes, pine flatwoods, and salt marshes. It’s home to endangered species such as the Choctawhatchee beach mouse, Gopher Tortoise, and Loggerhead Sea Turtles. Established in 1968, the park has grown into a hub for conservation, offering a balance between public access and protecting fragile habitats.

Key Takeaways:

- Unique Features: Includes Western Lake, a rare 214-acre coastal dune lake, and a mile-long beach vital for nesting sea turtles.

- Conservation Efforts: Focus on habitat restoration, prescribed burns, and controlling harmful species like feral hogs.

- Visitor Guidelines: Stick to trails, avoid disturbing wildlife, and follow Leave No Trace principles to preserve its delicate environment.

- Community Role: Groups like Friends of Grayton Beach and state programs have fought to protect this area from development.

Whether you're hiking, birdwatching, or simply enjoying the pristine shoreline, every visitor plays a role in preserving this natural treasure for future generations.

Grayton Beach State Park || Campground, Beach, and Amenities || Santa Rosa Beach, Florida

History and Establishment of the Park

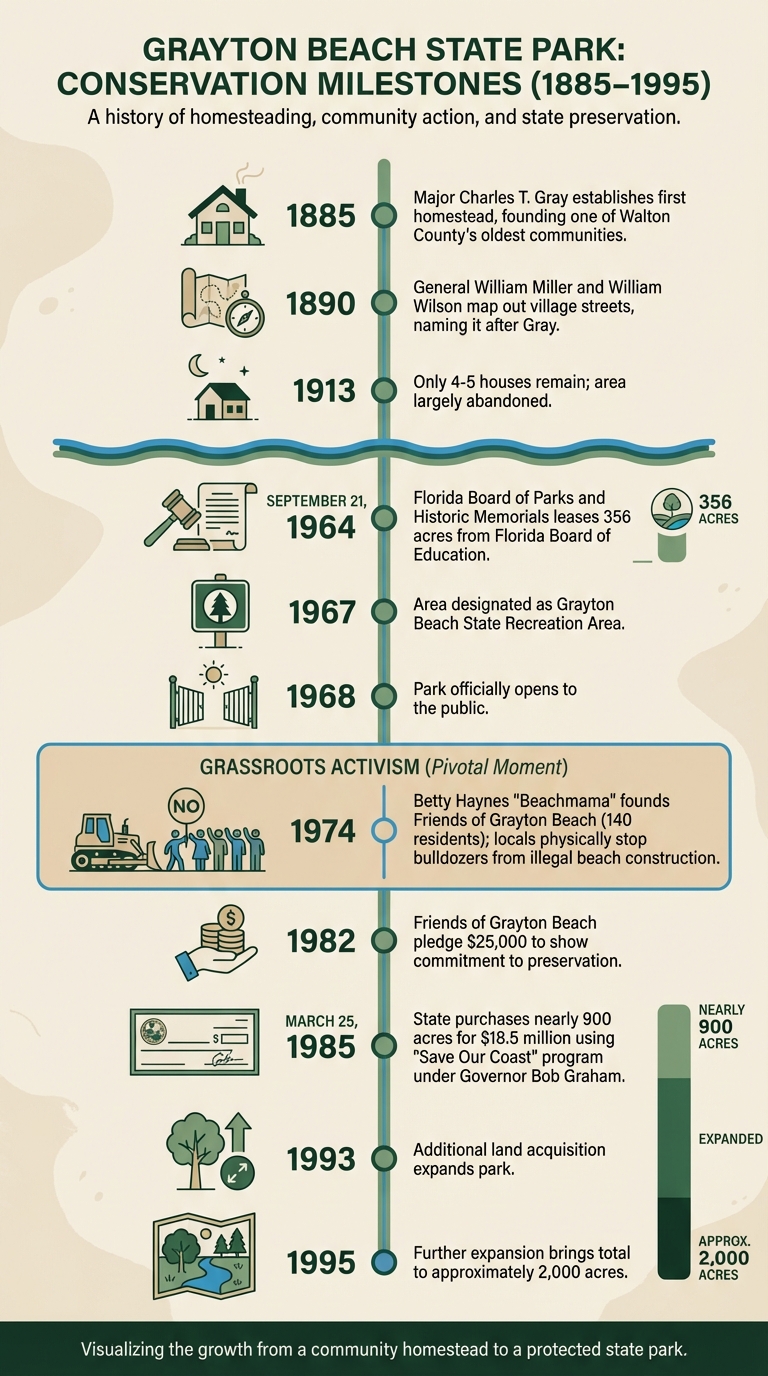

Grayton Beach State Park Conservation Timeline 1885-1995

From Coastal Town to State Park

Grayton Beach’s story begins in 1885, when Army Major Charles T. Gray established the area’s first homestead, making it one of Walton County’s oldest communities. By 1890, General William Miller and William Wilson mapped out the village streets, naming the community after Gray. Despite this early development, the area remained remote and sparsely populated. In fact, by 1913, only a handful of houses dotted the landscape. Van R. Butler, an early advocate for the village, later remarked, "People had pretty much abandoned the place... There were just four or five houses". This sense of isolation set the stage for a later push to protect the area's natural beauty.

The transformation from a quiet village to a state park began on September 21, 1964, when the Florida Board of Parks and Historic Memorials leased 356 acres from the Florida Board of Education. By 1967, the area had been designated as the Grayton Beach State Recreation Area, officially opening to visitors in 1968. These early steps laid the groundwork for the conservation efforts that would define Grayton Beach in the decades to come.

Key Moments in Conservation History

A major turning point for the park came in 1985, following nearly a decade of grassroots activism. In 1974, Betty Haynes - affectionately called "Beachmama" - founded the Friends of Grayton Beach. This group of about 140 dedicated residents fought to prevent condominium development in the area. That same summer, Haynes, Bibba Jones, and other locals physically stopped bulldozers attempting illegal construction on the beach. Their persistence eventually led to a breakthrough: Governor Bob Graham utilized the "Save Our Coast" program to negotiate a deal with the FDIC. On March 25, 1985, the state purchased nearly 900 acres of beachfront, dunes, and forest land for $18.5 million. The Friends of Grayton Beach even pledged $25,000 of their own money in 1982 to show their commitment to preserving the area.

Several key milestones highlight the park’s journey:

| Date | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 1885 | Major Charles T. Gray establishes first homestead |

| September 21, 1964 | State acquires initial 356 acres |

| 1968 | Park officially opens to the public |

| 1974 | Friends of Grayton Beach founded; residents block bulldozers |

| March 25, 1985 | State purchases 900 acres for $18.5 million |

| 1993, 1995 | Additional land acquisitions expand park to ~2,000 acres |

Governor Bob Graham later praised Van Ness Butler Jr., a local property owner who initially opposed the Friends of Grayton Beach but eventually became a key supporter. Graham referred to Butler as the "father of the project" for his efforts in working with state officials. Since its creation, the park has grown from its original 356 acres to roughly 2,000 acres, providing a natural barrier against large-scale development.

Conservation Programs and Initiatives

Habitat Restoration Projects

Grayton Beach State Park is a key participant in the Panhandle Dune Ecosystem Restoration (PDEP) project. This initiative, led by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the University of Florida, focuses on replanting native dune vegetation. These efforts not only strengthen the park’s natural defenses against storms but also create essential habitats for species like the Santa Rosa beach mouse. By interplanting native species, the team stabilizes dunes and provides forage areas. Visitors can even track the progress of native plant regrowth through photo stations set up at the park.

Another critical effort is the protection of Western Lake, a rare coastal dune lake. This project, supported by the RESTORE Council's 2026 Funded Priorities List, aims to improve water quality and restore natural hydrologic flow. Adam Blalock, Deputy Secretary of Ecosystems Restoration at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, highlighted the importance of these efforts, stating, “Florida is taking bold steps to protect this remarkable region for generations to come through strategic initiatives focused on improving water quality, restoring hydrologic flow and enhancing coastal resilience”.

These restoration projects also serve as a foundation for broader ecosystem management practices, including controlled burns.

Prescribed Burns and Ecosystem Management

Controlled burns are essential for maintaining ecosystems like coastal forests and flatwoods, which thrive on periodic fire. These burns prevent woody shrubs from overgrowing, which can block sunlight, harm native plants, and disrupt soil conditions. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection oversees this process as part of the park’s Unit Management Plan, a science-driven approach that also includes public input. Since 2019, over $400 million has been allocated to park infrastructure, including ecosystem management efforts.

Invasive Species Control

Managing invasive species is a top priority for the park. Rangers and biologists use a combination of hand removal, mechanical treatments, and targeted herbicides to address invasive plants and animals [23, 25]. Feral hogs, introduced centuries ago, are a significant challenge due to their destructive rooting behavior. To control their population, the park employs organized hunts, baited traps, and exclusion fencing, protecting sensitive habitats from further damage [24, 25].

| Control Method | Description | Common Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Hand Removal | Manual pulling to prevent seed dispersal | Coral Ardisia, Air Potato |

| Mechanical | Clearing dense thickets with equipment | Hydrilla, Brazilian Peppertree |

| Chemical | Applying herbicides to specific plants | Various aquatic and terrestrial weeds |

| Biological | Using natural predators like insects or fish | Melaleuca, Hydrilla |

| Trapping/Hunting | Reducing populations of destructive animals | Feral Hogs |

Visitors also play a role by cleaning their gear, using local firewood, and reporting sightings of invasive species [23, 24]. These combined efforts help protect the park’s native species.

Protection of Threatened and Endangered Species

The park's conservation work extends to safeguarding habitats for rare and threatened species. For example, the Gulf Coast Solitary bee, which relies on Coastal Plain honeycomb head plants, finds refuge in the park’s protected areas. Other beneficiaries include the Santa Rosa beach mouse, which helps disperse seeds for dune vegetation, and the snowy plover, a state-threatened bird that uses the dunes as shelter during storms. Additionally, management plans focus on balancing visitor activity with the protection of nesting habitats for sea turtles and shorebirds. These measures ensure that both wildlife and visitors can coexist in this delicate environment. To help plan your visit responsibly, use our South Walton itinerary generator to organize your trip.

Visitor Guidelines for Conservation

Leave No Trace Principles

Protecting Grayton Beach State Park begins with respecting its delicate ecosystems, especially the dunes. Walking on these fragile structures can cause erosion and disrupt the habitat of the endangered Choctawhatchee beach mouse. Always stick to the designated dune walkovers and paths to minimize harm . Walton County Ordinance 2017-05 requires that all personal belongings - like tents, chairs, and toys - be removed from the beach each night. Items left behind between one hour after dusk and one hour before sunrise may be confiscated. Before leaving, remember to fill in any holes and smooth out sandcastles to ensure nesting sea turtles, active between May 1 and November 1, are not put at risk. Use the refillable water bottle station at the trailhead to cut down on single-use plastics, and refrain from taking sand, water, or vegetation from the park . If visiting at night during turtle nesting season, only use flashlight covers designed to protect the turtles. These small actions make a big difference in preserving the park's habitats and fostering responsible wildlife observation.

Wildlife Etiquette

To help protect the park’s wildlife, it’s important to avoid disturbing its sensitive species. Many shorebirds nest directly on the sand, leaving them vulnerable to disruption. Stay clear of all marked nesting areas and observe animals from a safe distance. Binoculars are a great way to enjoy sightings of Bald Eagles, Great Blue Herons, and other species without getting too close . Pets are not allowed on the beaches, and in areas of the park where pets are permitted, dogs must be kept on a handheld leash no longer than six feet. Owners should also clean up after their pets promptly, as violations can result in fines of up to $500 . Quiet hours, observed from 11:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m., help reduce stress on nocturnal wildlife.

Eco-Friendly Activities for Visitors

Grayton Beach State Park offers plenty of ways to enjoy its natural beauty while treading lightly on the environment. The park’s 4.5-mile hiking and biking trail winds through coastal forests and pine flatwoods, and staying on these designated paths helps prevent soil erosion and protects plants like sea oats . For a peaceful water adventure, try kayaking, canoeing, or stand-up paddleboarding on the 100-acre Western Lake. Keep in mind that jet-propelled watercraft are not allowed to maintain the lake’s pristine condition. As part of the Great Florida Birding Trail, the park is a fantastic spot for birdwatching. You can also deepen your connection to the environment by joining a ranger-led walk on the Flatwoods Trail (scheduled for February 28, 2026). For those looking to contribute to conservation efforts, consider joining local groups like Friends of Grayton Beach and Deer Lake State Parks or participating in initiatives like the South Walton Turtle Watch Program .

Conclusion: Preserving Grayton Beach State Park for Future Generations

How Visitors Can Support Conservation

Every visitor plays a role in safeguarding the 2,000 acres of coastal ecosystems at Grayton Beach State Park. One way to contribute is by supporting groups like Friends of Grayton Beach and Deer Lake State Parks, which focus on preservation and educational programs. When the park reaches capacity and temporarily closes, respecting these limits is crucial to protecting its delicate environment.

You can also make a direct impact by volunteering for beach cleanups or native plant restoration projects. Simple eco-friendly choices - like using reef-safe sunscreen to protect water quality or exploring the park's 4 miles of trails on foot or by bike - help maintain the park's natural balance . Even the $5 per vehicle admission fee goes directly toward conservation efforts.

These small yet meaningful actions collectively support the park’s mission to preserve its ecosystems for the future.

Long-Term Conservation Plans

Florida's Department of Environmental Protection is working on ambitious plans to secure the park’s future. Through the Great Outdoors Initiative (2024–2025), the focus is on expanding visitor amenities while safeguarding the natural environment. For example, parking areas will use gravel and sand to improve drainage, and future developments - including 10 additional cabins and recreation facilities like pickleball courts - will be carefully placed to protect sensitive areas like dunes and coastal scrub.

"The goal of the initiative is to expand public access by increasing outdoor activities and provide lodging while also maintaining conservation from the state." - Florida Department of Environmental Protection

A key priority is the protection of Western Lake, one of just 15 coastal dune lakes along Scenic Highway 30A and a rare natural feature found in only four countries worldwide . With Florida’s state parks generating over 50,000 jobs and welcoming nearly 30 million visitors in the 2022–23 fiscal year, Grayton Beach State Park exemplifies how sustainable tourism can preserve "The Real Florida" for future generations.

FAQs

Why are coastal dune lakes so rare?

Coastal dune lakes are uncommon natural features, forming only under specific geological conditions found in select locations around the world. These include areas like Northwest Florida, Oregon, South Carolina, Madagascar, Australia, and New Zealand. These lakes emerge within dune ecosystems where sand dunes capture freshwater, which occasionally blends with saltwater from nearby bodies like the Gulf of Mexico. This creates a sensitive brackish ecosystem. Their scarcity underscores the need to protect and preserve these fragile environments.

How do prescribed burns help the park?

Prescribed burns play a key role in keeping Grayton Beach State Park's ecosystems thriving. These carefully managed fires replicate the effects of natural wildfires, helping to clear out dense vegetation, refresh the forest floor, and sustain habitats that depend on fire, such as coastal dune lakes and forests. By reducing the risk of uncontrolled wildfires, encouraging the growth of native plants, and restoring ecological balance, these burns create a safer and healthier environment for both the park's wildlife and its visitors.

How can I volunteer for conservation here?

If you're looking to get involved at Grayton Beach State Park, consider volunteering for events like the longleaf pine restoration project happening on February 3, 2024. Another option is to connect with the Friends of Grayton Beach State Park, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting conservation initiatives in the park.

For more details on how you can help, you can call the park directly at (850) 267-8300. You can also reach out to the Friends group through their social media channels or by using their mailing address.